A study of Wolf and Dog facial features to develop a nonverbal language lexicon

“Man has great power of speech, but the greater part thereof is empty and deceitful. The animals have little, but that little is useful and true; and better is a small and certain thing than a great falsehood.” – Leonardo da Vinci, Notebook, circa 1500

Background and Justification

Wolves (Canis lupus) and their domesticated form, Dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) demonstrate four types of communication:

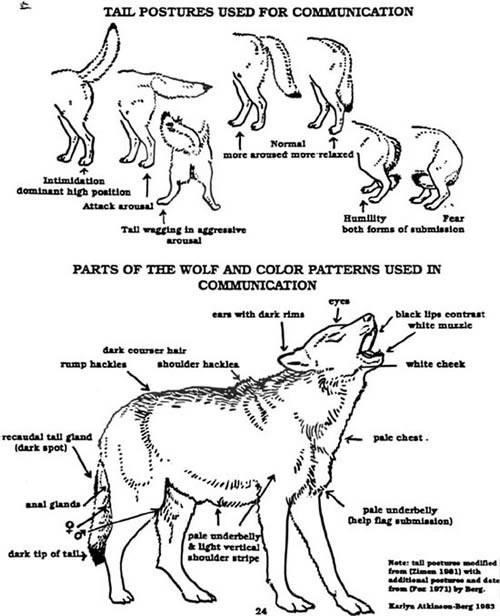

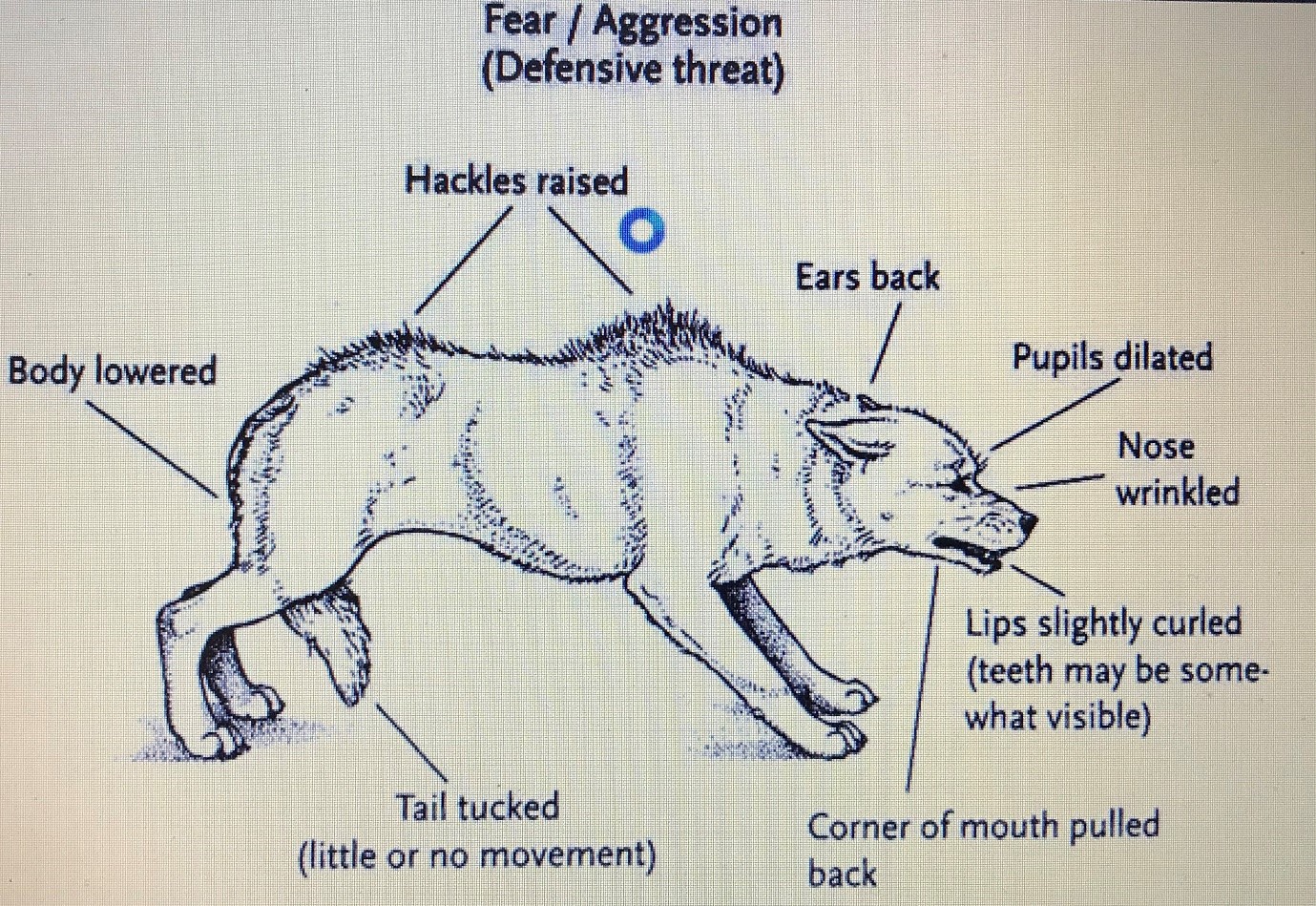

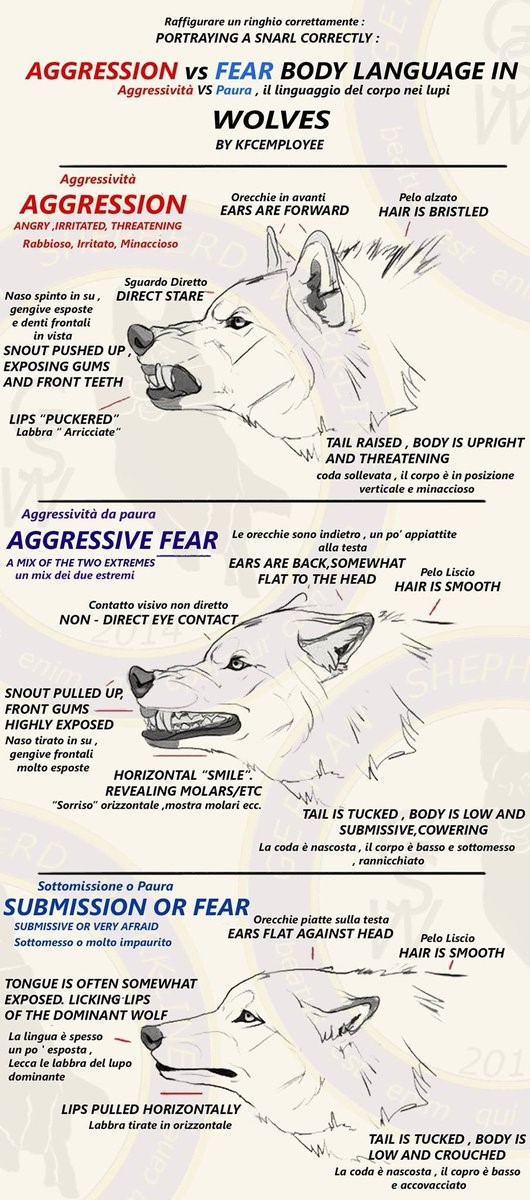

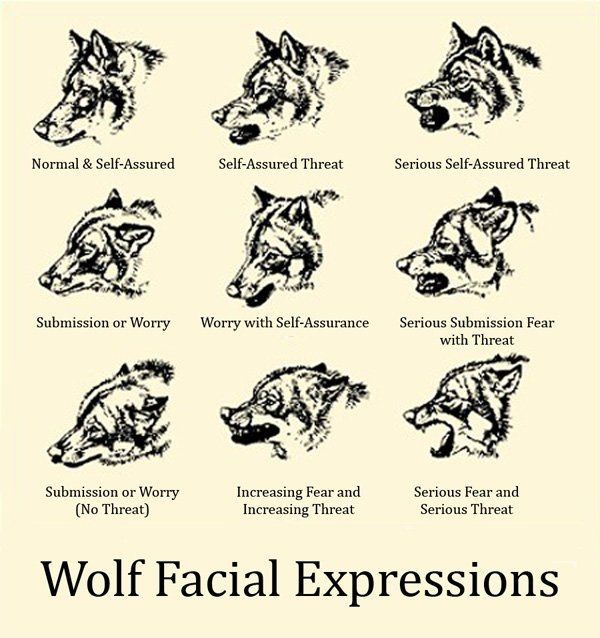

- Body language (Images 4, 5, 6)

- Vocal (https://www.livingwithwolves.org/about-wolves/language/#vocal)

- Scent (https://www.livingwithwolves.org/body-language-of-wolves/#scent)

- Facial expression (Images 5, 6, 7, 8).

The first three types have been well researched and documented (Abrantes, Morgan, Warner). Facial expression, on the other hand, has been given only rudimentary coverage, by both the scientific and Dog owner-breeder communities. Images 5 to 8 below illustrate the extent of our knowledge.

The knowledge vacuum creates a dilemma for animal behaviorists, Dog trainers, and pet owners, for these essential reasons:

- Body language, vocalizations, and scent are direct and generalized types of communication. They lack the subtleties that we humans enjoy with our rich and varied vocabulary.

- When the subtleties of communication cannot be conveyed, frustration and misunderstanding can result, which could lead to conflict. This is a common issue for humans interacting with Wolves or Dogs, and it is nearly always a factor in Wolf-Dog confrontations.

- In face-to-face interactions, body language, vocalization, and scent are often non-factors, as they are either preliminary forms of communication, or they require time and perspective to be conveyed.

An understanding of the language of facial expression holds the potential for addressing all three of the above-portrayed issues. With humans, facial expression automatically and spontaneously articulates and conveys the nuances of feeling, desire, and intent (Sandoval); and the same appears to be true with canines.

Beneficiaries

Those who could find direct value in expanded knowledge of canine facial expression include:

- The broad range of canine researchers

- Wolf sanctuary and animal shelter staff

- Dog trainers and owners

- Anyone caught in a confrontational situation with a canine

- Human facial expression researchers could apply canine research gains

Other likely interest groups:

- Indigenous people who have a cultural/spiritual connection with Wolves

- Animal behaviorists

- National forest and park staff

- Endangered and protected species specialists

- Zookeepers

- Trappers, Animal control and law enforcement personnel

- Outdoor journalists and writers

- The segment of the general population that enjoys nature and knowledge of animal behavior.

Aims and Objectives

The Facial Language Research Project (hereafter referred to simply as Project) is focused specifically on the vocabulary and grammatical structure of Canis lupus facial-feature-based communication, with the intention of creating user-friendly lexicons for both Wolves and Dogs.

Learning a new language takes two forms: mastery of its vocabulary and grammatical structure, and absorption of its cultural context. The two forms together constitute what is commonly referred to as a living language (cite). With vocabulary and grammar alone, a language is unable to convey the qualitative aspects of communication, which include aesthetics, depth of meaning, a poetic sense, and quality of relationship.

It is to be stated in the resultant lexicons that their proper usage can only be affected with a basic understanding of Wolf/Dog biology and culture. To assist in meeting that need, a list of recommended reference materials will be provided in the lexicons.

The final products of the Project are to include:

- A Wolf/Dog facial expression dictionary and grammar, in printed and digital form.

- Supplemental audio-visual materials.

- A PowerPoint workshop presentation.

All materials are to be made available to any interested party, in the most efficient and economically feasible ways possible. To maintain quality control and the ability to monitor revisions and updates, the Brother Wolf Foundation and all other research partner institutions will retain the copyright privileges to all materials generated by said Project.

Research Methodology

This section provides an outline of theoretical resources to be drawn upon, the advantages and limitations of the research approach, and a listing of research partners.

1. Research Approach

The science of facial feature analysis is in its infant stages. Our approach is to begin with a meta-analysis of to-date analytical, experimental, experiential, and theoretical material on the subject. Once completed, the analysis will provide the foundation for the Project. t.

2. Unique Challenges

One basis of comparative research is typology, which by scientific definition is classification according to general type.(Cite) With the Wolf, the following typological features of relevance to the Project manifest consistently in around 90% of the population(Cite) (see Images 1 & 5):

- A coat with various shades of black, silver, white, and auburn.

- Differences in pattern and texture that run from smooth milky white to grizzled and shaggy.

- Erect ears.

- Distinctive eyebrows.

- Flared cheeks.

- White neck and cheeks framing the muzzle.

- Dark-rimmed ears, teeth, eyes, cheeks and neck.

Virtually all Dogs lack some, most, or all of the above features — a hurdle which must be successfully negotiated in order to undertake relevant comparative analyses and arrive at deductive conclusions. Further, the absence of the differentiations in a Dog’s face (see Image 2) that are evident in a Wolf’s may limit a Dog’s the facial-feature based vocabulary and grammar structure, and thus the ability to engage in subtle and complex expressions of feeling and intent.(Cite) That may be why Dogs experience high levels of neurosis; rely heavily on barking, where Wolves seldom bark; and resort more to submissive and aggressive behaviors than do Wolves.(Cite)

Due to the fact that a Dog’s inability to utilize the full range and potential of canine communication is the result of human genetic manipulation, ethical and philosophical issues may arise, such as:

- Can we give Dogs back some of the ability to communicate that we took from them?

- Are Dogs psychically capable of taking it back?

- Would they choose to do so if it meant they would no longer remain Dogs?

3. Research Methods

To include, but not be limited to:

- Computer analysis of varied canine facial expressions, from video footage.

- Blind observation, utilizing a predetermined data-collection process.

- Structured interactive scenarios, to elicit specific psycho-emotional responses.

- Comparative analysis of Wolf and Dog facial features.

- Comparative analysis of facial features of representative Dog species.

4. Available Resources

Vultology, the study of nonverbal facial feature-based human communication, is currently being developed primarily by Juan E Sandoval. Based on his earlier work in cognitive typology (Sandoval, 2016), vultalogical research shows great promise for cross-application to canines. Development of computer-based facial recognition that relies on feature analysis systems began in the 1960s and today is being broadly applied in a number of fields, most notably security and crime detection. Biometric Facial Comparison, Amazon Rekognition, Betaface, and BioID are among the most notable. We will avail ourselves of any of these systems and related research that will lend support to the Project.

Image 3 was generated to accentuate the various vultalogically-relevant facial features a Wolf uses to express emotion and intent. The image will be used for identifying and differentiating facial features for research and lexicon development purposes, and for Project presentations.

5. Potential Limitations

The availability of research animals is currently seen as our most notable hurdle to overcome. Initial discussions with Dog owners indicate a general willingness to participate, and video footage of both Dogs and Wolves in varied interactive settings is readily available. Collecting additional data from either wild or captive Wolves is currently seen as a potential major logistical challenge.

6. Research Staff and Partners (all positions other than those stipulated are either not yet filled or pending)

Cosponsoring Organizations (in process or not yet queried)

- Wolfcenter GbR (wolfcenter.de) in Germany

- Wolf Science Center (wolfscience.at) in Austria

- International Wolf Center

- Timber Wolf Alliance

- Wildlife Science Center

- Wolf Conservation Center

- Wolf Education and Research Center

Staff Positions (no positions yet filled)

- Project director

- Research coordinator

- Academic and field researchers

- Grant writer

- Data processor

- Graphics artist

- Research report writer-editor

- Educational presenter

- Volunteer coordinator

- Volunteers to serve in various capacities

Consultants

- Hugh Jansman, Wolf biologist for Holland’s Animal Ecology Environmental Research Center (WENR) – confirmed

- Dr. Marianne Heberlein, Head of Science of Core Facility & Head of Animal Team Wolfscience Center (WSC), Austria – confirmed

- Dr. Lina Oberliessen, Senior Animal Trainer & Deputy Scientific Coordination

Wolfscience Center (WSC), Austria – confirmed - Barbara O’Brien, animal photographer – confirmed

- Tamarack Song, Wolf behaviorist and BWF founder – confirmed

- Teo Alfero – not yet queried

- Frans DeWaal – not yet queried

- Jim & Jamie Dutcher – not yet queried

- Dr Dorit Fedderseen-Petersen – not yet queried

- Temple Grandin – not yet queried

- Dayna McGuire – not yet queried

- Rick McIntyre – not yet queried

- L David Meech – not yet queried

- Juan E Sandoval – not yet queried

- Cat Warren – not yet queried

- Adrian Wydeven – not yet queried

7. Timetable and Report Schedule

Generating a Project development schedule is to be the first order of business for key staff members once they are in place. The Annual Report is to be formally presented. The educational presenter is to develop a PowerPoint Project presentation, with levels suitable for primary school, secondary school, and university-research audiences, and for the general public.

8. Contact Information

office@brotherwolffoundation.org; 715-546-8080

www.brotherwolffoundation.org

7124 Military Rd., Three Lakes, WI 54562

References

Research Papers

Nicolene Swanepoel, Insights into canine communication and interspecific misinterpretations, Published Online:1 Jan 1996https://hdl.handle.net/10520/AJA02590069_344

DJ Mellor, Tail ddocking of canine puppies: Reassessment of the tail’ s role in communication, 2018

J Bräuer, K Silva, SR Schweinberger, Communicating canine and human emotions: commentary on Kujala on canine emotions-Animal Sentience, 2017 – pure.mpg.

S Somppi, H Törnqvist, L Hänninen, C Krause, Dogs do look at images: eye tracking in canine cognition research. Animal Cognition, 2012-Springer

D LePan, Canine English: Communication in André Alexis’s Fifteen Dogs – Annual Conference of the Northeastern Modern …, 2018 – papers.ssrn.com

Á Miklósi, J Topál, What does it take to become best friends? Evolutionary changes in canine social competence. – Trends in cognitive sciences, 2013, Elsevier

Vergallito, Mattavelli, Lo Gerfo, et al, titled Explicit and Implicit Responses of Seeing Own vs. Others’ Emotions: An Electromyographic Study on the Neurophysiological and Cognitive Basis of the Self-Mirroring Technique. Frontiers of Psychology, March 31, 2020

Books

S Coren, How to speak dog: mastering the art of dog-human communication, 2001

Roger Abrantes , Sarah Whitehead, et al. Dog Language: An Encyclopedia of Canine Behavior, 1997

Lili Chin, Doggie Language: A Dog Lover’s Guide to Understanding Your Best Friend , 2020

George Morgan, How to speak dog: a guide for understanding dog’s body language and behavior, 2022

Scott MacConachie, Jaime Bessko, et al., How to read a Dog’s Body Language: Made Easy, 2019

Trevor Warner, Dog Body Language: 100 Ways To Read Their Signals , 2017

Aude Yvanès, Understanding Dog Language – 50 Points, 2013

Kevin Arts,, Understand your Dog Like if he talks: A Full guide to understand your Dog, 2022

David J Kurlander and Shaun L Smith, Through the eyes of a Canine: How changing your perception and understandingthe emotional lifeof your dog can create a stable and harmonious pack. Winds of Fate, 2021

Brenda Aloff, Canine body language: A photographic guide interpreting the Native language of the domestic dog, 2005

Barbara O’Brien, Dogface. Avery, 2014

Juan E Sandoval, Cognitive Type: The Algorithm of Human Consciousness as Revealed by Facial Expressions. Nemvus, 2016